Welcome Flats are without a doubt welcome after the long climb from near sea level. There is a

hut here, and it is spacious and very well built for being isolated by 17 kms of bush. There is nothing quite like the feeling of being out in the middle of nowhere and coming upon something as civilized as shelter. It sleeps 32 on cots, has a good kitchen area with water from cisterns, coal/wood stove for heating, and natural sulphur springs hot pools a minutes walk down a small path. There are a total of four pools with varying temperatures depending on the route the inflow takes - the largest is about 2 feet deep and is maybe the second hottest, with a good deal of water flowing directly in from the springs themselves, 20 feet away. I soak in the pools for a while, watching the mountains in the mist and rain, before returning to the hut to make dinner.

In the morning I wake up to a beautiful day. The clouds have opened up a bit and the sun is beginning to stream into the valley as we start our hike toward Douglas Rock Hut and maybe Copland Pass. The peaks along this part of the valley are even higher, and glaciers and snowfields can be seen on many of them. Welcome Flats extends for maybe 2 or 3 kms up the valley and is like a high grassy pasture. The clouds break enough to catch a glimpse of the highest peaks of the area, in the far end of the valley where we are headed. Winds blow snow trails off the fluted points catching the morning sun light. To our left now, the Copland River relaxes on the Flat, mist rising off the cloudy blue water. We catch up with Cynthia, a camper we met a Welcome Flat Hut, and end up hiking with her for most of the day.

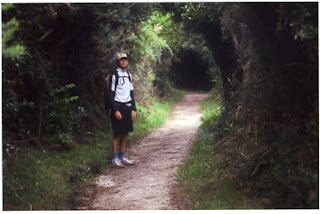

(Part way up Copland Track - photo by Cynthia)

The trail runs back into rainforest and suddenly our views of the peaks are cut off except for small breaks in the bush or at spots where steep bolder filled creeks churn through the forest and hold the canopy back. Mosses cover the ground on either side of the track, run over roots and up into the branches of the trees. Most trunks have a thick fur of light green moss. On a foot bridge, I get a view out across the valley to my left. The chain of peaks break and a high hanging valley joins the one we are in. On each margin of the valley, white ribbons of water and spray step down to join the Copland River, and in the far distance, over the horizon of the valley, rise more peaks and snowfields supplying these two creeks. I can hardly believe the beauty of this spot, thick rainforest covering slopes as far as I can see, a stark contrast to the barren grazing lands of Molesworth. Avalanches and mudslides mark where the mountains are slipping back on themselves, while above tree line, layers of exposed rock, pointing off at 45 degrees from horizontal show how this earth has risen, some of the fasted rising peaks in the world.

We reach Douglas Rock Hut after about 3 hours, eat part of a lunch, and head further up the valley. I am amazed at the size of the Copland River, it still holds quite a lot of water here, and we are over 20 kms up this valley. The gradient of the river has increased again, and the bed is full of house and car sized boulders which the river slams into head on, or sometimes slips underneath. Less than an hour from Douglas Rock and we are into what seems like a high alpine bush or grassland. We have left the trees, and there is no longer a full canopy overhead. Tussocks line the trail and rise to eight feet or more in height. Mixed in are small deciduous shrubs or trees no bigger than my arm. Occasionally we step around ragged yellow flowers that droop under the weight of the dew. The valley turns off to the northeast. We sit on boulders in a small creek, eat the rest of lunch, and decide we will try to follow the valley up to it's terminus at Copland Pass. I feel like I have already made it, have seen what makes me content while sitting on these boulders. The knowledge of this place is what I've come for, but I will go on to the pass with Dan as well.

Again we cross a high flat stretch. The walls of the valley have become more U shaped, and overhead hanging glaciers peer over sheer cliff walls and their outflows make long misty waterfalls that trail off in the wind. We round a bend and finally see the end of the valley - a huge bowl with what appear to be cliffs rising on the three sides. Two tarns of the brightest blue sit in depressions carved out by the glacier, and the Copland River begins where it breaches the dam made by the terminal moraine. Other moraines, older, skirt the north side of the valley, now beginning to grow vegetation. The newest are made up only of scree and boulders of grey rock.

(Approaching Copland Pass)

As we reach the end of the valley, we see that it is not vertical cliff. We climb up and out, traversing back and forth across a ridge bounded on either side by deep, narrow gorges, carved by the glacial outflow streams. We come closest to the one on the northern edge, in spots walking right along the edge, glancing down at the potholes and waterfalls of the little stream. The last one visible falls away into nothing, its bottom hidden from our view. The alpine vegetation has almost completely disappeared and the trail criss-crosses the grey scree fields, making the grey kairns which mark the path very hard to spot at a distance. Small pockets of snow come in to view as I reach the last pitch. I have lost the trail altogether, but Dan has headed off up to my left, so I work my way towards him. Before I get too far he retreats and says the scree is far too unstable to make it up the left side. As we traverse the opposite way a large rock I'm standing on begins a creeping descent and I hold my breath while it slows, and stops. The climbing is not technical, but it is still quite a long hike out, so an injury could be a real hassle.

At the end of the traverse we are able to drop into a slight depression that has hidden the trail and the more stable rock, and we head up again. We crest the ridge and see a few small snowfields between us and the main mountain divide. We make a quick dash up and have a look over the edge, in to the valley on the eastern side of the Alps. It will be quite some time until we make it to that part of the island on our bikes. Within 15 minutes the pass has been covered by clouds and the wind picks up. It is time to head down, looking out over the valley, to the clouds floating over the Tasman Sea to our west, the Copland River just a ribbon through grey boulders and dense green forest.

(Descending from Copland Pass - Photo Dan Cantrell)

We are back at Douglas Rock Hut by about 9 pm, for a total of over 12 hours of hiking. It has been an incredible day. We eat dinner with the western light streaming in on the glaciers and the high peaks, later the near full moon hangs framed between spires to our north.